Samuel George on why commodity-led growth may not be over just yet

There is an interesting article in The Economist this week about commodities and Latin America. Some of it is predictable—that the end of strong commodity prices is nigh, and that we are at “the twilight” of the commodity boom that was predicated on Chinese and Indian industrialization.

These have become rather mainstream (and perfectly reasonable) arguments, the likes of which No Se Mancha has covered previously.

The Economist article does deserve credit for pointing out that a number of Latin American countries have used the boom to position themselves to withstand less favorable terms of trade, as well as macroeconomic turbulence stemming from tighter monetary policy in the US.

The article also suggests that the real concern is underwhelming growth, as opposed to economic deterioration. This is an important point.

It’s a good and recommended read. (Though the piece’s take-down of Mexican productivity seems bizarre given the same newspaper’s recent “Mexico Rising” articles that suggest a resurgence in Mexican competitiveness—but consistent readers of the The Economist are, or course, accumsted to such vicissitudes).

So is the era of commodity-led growth really over?

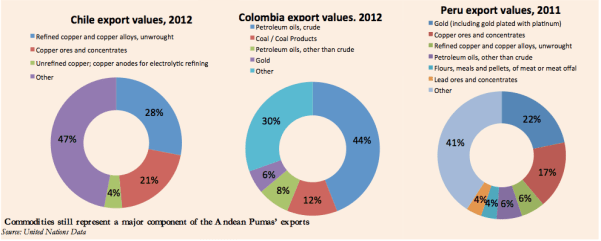

To be sure, the six major South American economies (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Peru and Venezuela) have greatly benefited from the highest commodity prices observed since World War II.

Should these falter, the argument continues, so too would Latin American growth. Even if prices remain strong, overreliance on commodity exports threatens to prevent the linkages South American countries need to expand beyond resource reliance.

And basic theory of supply and demand suggests that commodity prices may soon come back down to earth.

On the one hand, demand may be in decline. As Chinese growth tapers, and as OECD demand for Chinese goods remains sluggish, the Dragon no longer stockpiles copper and ore reserves, instead pursuing a “hand-to-mouth” buying pattern.

On the other hand, commodity supply has increased. New investments inspired by boom-era prices are only now coming online, portending expanded supply. Credit Suisse forecasts that global copper production will increase four percent annually between 2012 and 2015, leading the investment bank to conclude that “copper scarcity is a thing of the past.”

Yet the unwinding of the boom need not be cataclysmic.

For one thing, commodity exports will not disappear overnight. Chinese growth may decline, but seven percent annual expansion over the next five years (as forecast by the IMF) is not exactly a depression.

Moreover, demand from other resource-starved Asian countries will likely increase. Between 2000 and 2010, mineral imports to India, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand all averaged more than 20 percent annual growth.

Even the bearish forecasts have copper prices above the average price between 2003 and 2008, which were years of strong growth for Chile and Peru.

The pundits make it sound like this will be Peru in three years (the photo is from a former Chilean mining site, now a ghost town)

Towards smarter commodities

In terms of linkages, conventional wisdom holds that commodity exports generate few forward and backward employment opportunities.

Where raw resources are simply withdrawn from the earth and shipped abroad, few “downstream” jobs are created, little technology is needed and a country does not cultivate spillover knowledge.

But perhaps this is an over-simplification.

According to a World Bank background research paper, Latin American metals, for example, are differentiated enough “to create a high degree of intra-industry trade, implying the exchange of distinct varieties…[creating] the potential for specialization in, and upgrading to higher quality, higher values within product categories.”

As with industrial goods, commodities pass through a series of production phases as they are refined, for example, from iron ore to steel or from oil to gasoline. This process requires advanced technology.

The problem is that the technology has historically been housed elsewhere.

For example, Chile, the world’s largest producer of copper, builds only one percent of the world’s fabricated copper products. Mexico exports crude oil to the US and imports refined fuel.

As more stable Latin American countries, such as the Pacific Pumas—apologies for the obligatory plug 😉 –develop internal investment muscle, and as they continue to earn the faith of international developers, more downstream linkages could occur domestically.

Chile has already set the stage, moving from an imitator to an innovator in exporting wood pulp and wine (as opposed to logs and grapes).

If other countries can follow suit, perhaps natural resources can be a foundation for an expanding economic ecosystem, as opposed to the first and last words in Latin American development.

Samuel George is a Latin America specialist working in Washington DC.

Read more from Samuel HERE

Pingback: Wietwet Uruguay, Grondstofprijzen Zuid-Amerika | Sargasso

The FT’s John Paul Rathbone just posted on this topic as well on beyondbrics…check that out here: http://blogs.ft.com/beyond-brics/2014/03/31/after-latin-americas-boom-years-anticipating-the-deluge/#axzz2xdgIq1TE