James McBride on presidential systems in the Americas

Juan Linz was probably the most prescient commentator on US politics that Americans have never heard of.

Linz, a scholar of comparative political institutions, passed away last week at the age of 86. A Professor Emeritus of Yale University, he was well known in Latin America for his incisive analysis of the region’s transitions from authoritarian to democratic regimes that began in the 1980s.

The dynamism of Latin America’s developing democracies threw a bright spotlight on Linz’s main concern: the role of institutions in channeling political change.

For him, different institutional structures provided different incentives for either conflict or cooperation, leading to either compromise or crisis. Institutions could thus make or break democratic transitions, especially in fragile young states.

Linz was particularly skeptical of presidential systems – like those in Latin America and the United States.

Perhaps this was his most defining position. In his classic 1990 essay “The Perils of Presidentialism”, he argued that presidential systems are inherently more susceptible to political gridlock, crisis, and breakdown. For stability, new democracies should look, instead, to the parliamentary model.

The argument, at its most basic, goes like this: By dividing authority between an executive and a legislature that are each independently elected, presidential systems create a dangerous “dual legitimacy”. That is, there is no agreed upon way to settle a standoff between a congress and a president. In Latin America, such conflicts often prompted the military to intervene.

By contrast, parliamentary coalitions only last as long as they can pass major legislation – a coalition either finds a compromise solution, or new elections will be called and the government will be replaced by a new one that can. No need for the army to leave its barracks.

Thus, parliaments exhibit short-term instability but avoid major crisis in the long term. Presidential systems offer superficial stability, but will more often come to the brink of truly dangerous crisis.

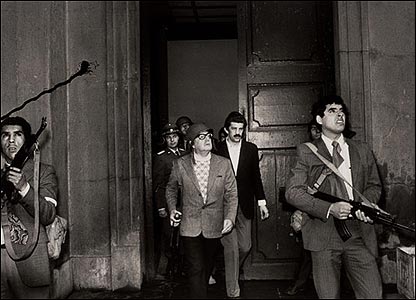

When obstructionist congress refused to play ball, even firearms and hard hats could not save Chilean democracy

In other words, presidential systems break because they can’t bend.

Linz was writing in 1990, but Latin America’s more recent history only further proves his point. Writing in 2004, Georgetown professor and former State Department official Arturo Valenzuela catalogued all of the region’s “interrupted presidencies”, in which fourteen different presidents were forced to end their terms early due to political gridlock, mass protests, and plummeting legitimacy.

If that sounds painfully familiar to those following the current government shutdown in the US, it is no accident.

The US, like Latin America in the 1990s, is facing an increasingly polarized electorate and the rising influence of extremist political factions. Conflicts between congress and the president are becoming sharper and less conducive to compromise.

Mirroring the outlook of many Latin American opposition parties, Congressional Republicans have come to see federal authority in general—and the Obama presidency in particular—as fundamentally illegitimate.

For them, compromise has come to mean traitorous complicity rather than prudent give and take.

They are, like many opposition movements in Latin America were a decade ago, increasingly willing to break unwritten rules of political cooperation and use whatever means available to defeat the president – including bringing the country to the brink of default.

Linz thought that the US was different because our political parties were less extreme and less rigid than in other countries. But that has clearly changed in the past two decades.

So what can the US learn from Latin America?

Linz always saw the US as the great exception to his rule, but in recent years he recognized that it was heading down the same path as the world’s more troubled presidential systems.

Unfortunately, the lessons from Latin America are not encouraging. Discussing places like Haiti and Paraguay, Valenzuela wrote that presidential systems “give rise to a logic of confrontation precisely because the president’s foes see a successful chief executive as bad for their own interests.”

This “logic of confrontation” explains the blanket opposition of Congressional Republicans. Presidential systems are so dangerous precisely because opposition parties have no incentive to compromise, nor much, if any, stake in passing major legislation.

Some in Washington are realizing that America’s crises are due to deeper structural issues.

Slate’s Matt Yglesias has recently drawn on Linz’s work to make this argument. He and others have also pushed for reforms to the worst aspects of the gridlock-promoting system – perhaps most notably the filibuster, whose use has grown drastically as Republicans have sought to grind the workings of government to a halt.

But the conventional wisdom in DC is in general still far too enthralled by the power of individual personality. The frustrating irony of presidential rule is that the Leader of the Free World wields, in practice, very little leverage over the legislative process. No amount of “charm offensive” or “presidential leadership” will change that.

In other words, President Obama has nothing of interest to offer Republicans – except, of course, his resignation (or maybe Malia?!).

This is why negotiations fail and government shuts down.

But Latin American presidents have seen this movie many times, and it never ends well. While the current crisis dominates the headlines, the US should begin thinking about how to avoid the next one – and the one after that.

James McBride is an Associate at Blue Star Strategies, an international consulting firm that advises corporations, governments, and institutions on government affairs and investment strategies.

Also by James

Blazing a Trail: Uruguay and A Shifting War on DrugsJustice in Guatemala: Dealing With Dictators

Film Review: Pablo Larrain’s No grapples with the nature of democracy

Pingback: The Eleventh Hour « Joshua Ryan Ziefle