James McBride on Chile’s new carbon tax

In September, Chile’s President Michelle Bachelet notched a huge political victory: the passage of a major tax reform that was one of her administration’s top three priorities.

The plan seeks to reduce Chile’s widening inequality by increasing spending on key social policies. Bachelet has proposed more than $8 billion in new funding for education, in particular, and the tax reform will finance that ambitious increase by raising corporate tax rates from 20 to 25 percent in the highest bracket. It will also close a number of loopholes, end corporate tax breaks for investments, and introduce new consumption taxes.

But lost in the broader sweep of reforms has been another measure that could have even more far reaching implications for Chile, and the world. That is the government’s approval, on September 26th, of South America’s first carbon tax.

Carbon: no longer priceless

What does this mean for Chile? Specifically, the measure will target the country’s largest power producers, the thermal plants with a peak capacity of at least 50 Megawatts (MW). As Reuters points out, that means the bulk of the tax will likely fall on the four largest power companies: Endesa, AES Gener, Colbun, and E-CL.

Beginning in 2017, the government will measure the carbon output from those emitters, and affix a fee of $5 per each ton of carbon dioxide. The idea is that even a modest tax will give emitters a financial incentive to find ways to minimize CO2 production on their own.

And it is, indeed, a very modest tax. When the Canadian province of British Columbia enacted its own carbon tax in 2008, it began with a rate of $9 per ton, and progressively raised it to nearly $27 per ton by 2012. Brookings argues for a plan that begins at $16 per ton. The IMF has pegged the total cost of climate change damages at $25 per ton, while other estimates range up to $85 per ton.

But, of course, politics is the art of the possible – and for a still-developing country like Chile, which struggles with some of the highest energy costs in the region, even a small energy tax brings controversy. As opposition groups argue, it will, at least in the short term, contribute to those high prices.

However, the exorbitant cost of energy – caused in large part by the bottleneck created by Chile’s need to import 96 percent of its oil and gas – is a major reason in its own right for government policy to be spurring energy production away from fossil fuels. A carbon tax makes cleaner forms of fuel more competitive, and incentivizes investment and research in alternative and renewable energies.

As Gariazzo Rodrigo Pizarro, chief of economics in the Environment Ministry, puts it, “We believe that changing the price allocation through taxes is enough to generate a greener economy.”

An economic threat?

But what about the effects on consumers and the broader economy, whose growth has been slowly but steadily weakening?

Again, the example of British Columbia is instructive. The BC government used its revenue to offset the attendant energy price increases by cutting taxes for low income workers, lowering taxes for small businesses, and providing a quarterly lump-sum energy rebate to consumers.

Chile, on the other hand, will direct the modest revenue of its plan – estimated at about $160 million per year to start – towards financing its education reform. Thus consumers won’t see a direct rebate, which could put the tax on shakier political ground.

When it comes to economic growth, the government may have less to worry about. A five year study of the British Columbia economy found that – even with its dramatically higher tax – there was almost no appreciable effect on GDP. At the same time, consumption of fossil fuels fell 19 percent compared with the rest of Canada.

And business groups are often less averse to a carbon tax than one might expect. Compared with more bureaucratic methods of reducing CO2 – like mandating a complex system of emissions standards for each type of vehicle, factory, or power plant – a carbon tax is compatible with smaller government.

As David Chavern, the COO of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, said in an interview last year: “A carbon tax is much more efficient, more neutral…it doesn’t pick winners and losers.”

(However, Republican leaders in Congress have been very eloquent on their potential support for such a tax: “No.”)

The global context

Chile is a country of just under 18 million people, with a GDP of under $300 billion, whose carbon emissions comprise a tiny fraction of the world’s output. How relevant, then, is its experience?

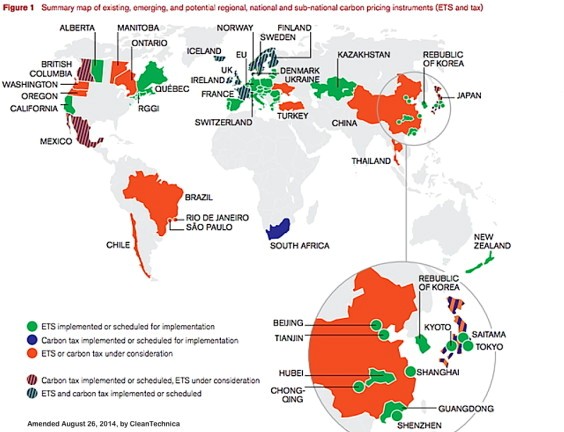

Besides pushing its own energy consumption away from fossil fuels, Chile’s carbon tax illustrates the broader decentralization of anti-climate change efforts. With the general failure of global diplomacy on the subject, countries, provinces, and cities around the world are doing what they can with the power they have. And in that effort, the power of example matters.

“Chile is not a great contributor to greenhouse gas emissions,” acknowledges Rodrigo Pizarro. “But we are very vulnerable. It is in our national interest to see significant commitments in terms of climate change.”

Up to now, a patchwork of some 40 countries and many additional local jurisdictions have managed to bring 12 percent of the world’s carbon emissions under some form of regulation. Each one, through trial and error, provides lessons for reformers elsewhere.

Latin American efforts to rein in carbon remain in their infancy. Mexico is the only other country in the region with a carbon tax – introduced in January 2014, it sets a range of prices that averages out to a charge of just $3.50 per ton. Brazil has toyed with a cap-and-trade like emissions trading scheme, and the city of Rio de Janeiro has developed its own proposal for a city-wide carbon trading market, but both of those plans have faced delays and tough industry opposition.

In the emissions trading scheme (ETS) model, instead of levying a flat tax on each unit of carbon, governments create a new market in which carbon permits are bought and sold. Theoretically, the supply of permits is then gradually restricted, raising the “price” of producing carbon to a desired level.

The ETS approach has shown mixed results. The most infamous example is that the European Union’s groundbreaking effort to reduce its carbon output to 20 percent below 1990 levels. Things started poorly in 2005 when the EU allowed too many permits. Then the recession reduced demand for energy and carbon prices plunged further. Between 2011 and 2013, EU prices fell from $30 per ton to below $10.

Demonstration effect

Other policymakers can learn from some of these drawbacks. Compared to a tax, ETS schemes are more complicated to set up, place more managerial responsibility in the hands of potentially dysfunctional political systems, and are more susceptible to the vagaries of international economic conditions.

At the same time, places as disparate as Kazakhstan, South Korea, New Zealand, Quebec, and California are going ahead with ETS programs.

China, especially, has placed a big bet on carbon trading markets. It’s 12th Five Year Plan, which ends in 2014, established ETS in seven cities or regions: Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Shenzhen, Chongqing, Guangdong, and Hubei. Qindao has also announced its plan to introduce a CO2 capping scheme.

And as China works through its plans to impose an additional pollution tax – which may or may not include carbon – it may turn out that the tax vs. cap debate is not either/or. Different governments with differing levels of authority and capacity will likely be better suited to one or the other.

When it comes to pricing carbon, the world is moving – if hesitantly. Chile’s experience will soon become another important data point in understanding the effect of such regulations on consumers, GDP growth, and the broader effort to shift toward less carbon-intensive economies.

James McBride is an Associate at Blue Star Strategies, an international consulting firm that advises corporations, governments, and institutions on government affairs and investment strategies. Find more of his writing at jelliotmcbride.com.

See more by James HERE

Pingback: Chile's Carbon Tax: The Price is Right? - James Elliot McBride | James Elliot McBride